library(dySEM)

#>

#> Welcome to dySEM!

#>

#> Please support your academic developers by citing dySEM; this helps us justify to our home institutions the time we spend on expanding and improving dySEM:

#>

#> Sakaluk, J. K., Fisher, A. N., & Kilshaw, R. K. (2021)

#>

#> Personal Relationships, 28(1), 190-226.

#>

#> https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12341

#>

#> dySEM is also heavily dependent on the lavaan package (please cite it too):

#>

#> Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling

#>

#> Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1-36.

#>

#> https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

#>

#> And should you use dySEM's outputParamFig() function, please be sure to

#>

#> also cite the semPlot package (upon which it depends):

#>

#> Epskamp, S. (2015). semPlot: Unified visualizations of structural equation

#>

#> models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 22(3), 474-483.

#>

#> https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.937847Introduction

Most users will follow a four-step process to use dySEM:

- Scrape Variable Information

- Script a Model

- Fit a Model

- Output Desired Values

Of these steps, scraping variable information is one of the most important, yet unintuitive, as researchers do not often take the process of naming their variables for granted.

In this short tutorial, we are going to focus on the patterns of

repetition that are present in the variable names in many data sets, and

provide a breakdown and vocabulary for the “anatomy” of these variable

names. Understanding the elements that make up a variable name will

therefore help you to apply more efficient names in your own dataset(s),

and to navigate the scraping step of using dySEM more

easily using a function like scrapeVarCross().

Effective Variable Name Styling

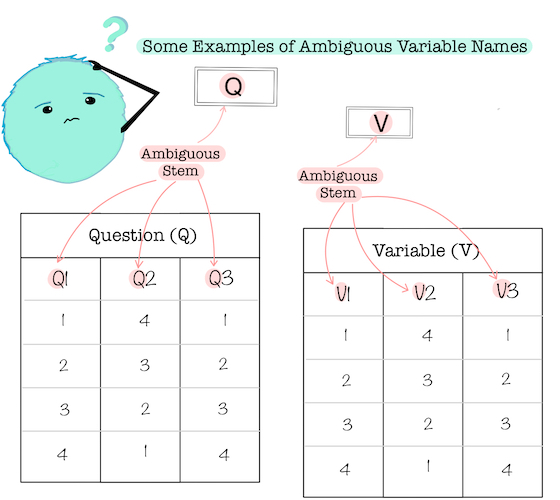

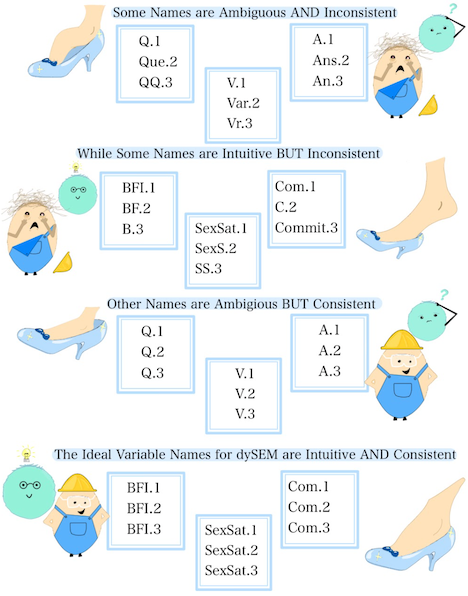

Try to remember the last spreadsheet of data you interacted with. Now think of the variables (i.e., columns) within it. The names of those variables could probably be categorized in terms of a few dimensions of styling, namely, the clarity and repetition of the variable name’s stem (i.e., the text content of the variable’s name). In terms of clarity, some variable name stems you thought of were probably ambiguous or cryptic (e.g., Q1, Q19_1)–you or someone else wouldn’t immediately be able to understand what kind of data was captured in that variable based on the stem alone.

Some Examples of Ambiguous Variable Names

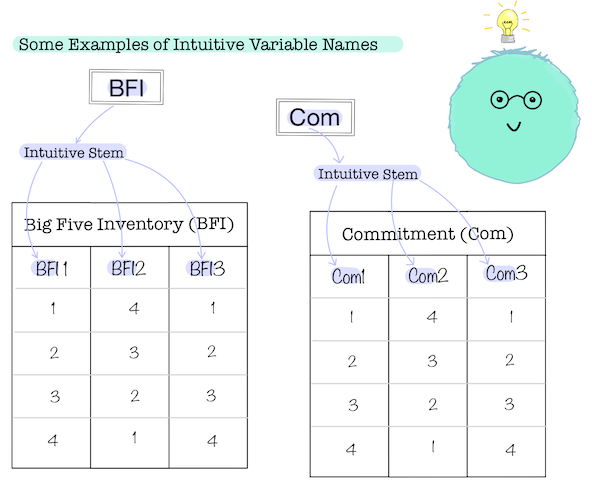

Other variable name stems, meanwhile, were probably more intuitive. Variables corresponding to the 18 Experiences in Close Relationships survey items, for example, might be named using the intuitive acronym of ecr, which could be more immediately recognized and understood by someone familiar with the study.

Some Examples of Intuitive Variable Names

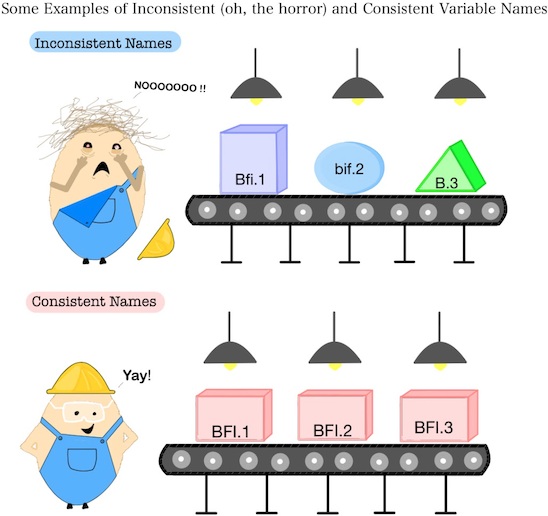

The second dimension, repetition, is sometimes so subtle you might not immediately recognize it as a feature of variable name stems (and an important feature at that!). Some variable names–even if they refer to a set of related variables–might be highly inconsistent or idiosyncratic. The same exemplar variables corresponding to the 18 Experiences in Close Relationships survey items might be named with different descriptive text in each variable name, or using different patterns of text casing or delimitation. This kind of inconsistent naming might strike you as unlikely to occur “in the wild”. We agree, and we have therefore developed dySEM accordingly, betting that they are the exception, not the rule. The point, however, is that inconsistent variable names are, strictly speaking, conceivable. But for the most part, we anticipate related variables will be named repetitiously: the stem, casing, and delimitation applied to one of many related variables will be applied to all.

Some Examples of Inconsistent (oh, the horror) and Consistent Variable Names

These two dimensions of variable name styling play important, but

different, roles when scraping variable information via dySEM.

Clear names are not essential for scraping functions (e.g.,

scrapeVarCross()) to work properly, but they will make for

quicker and less error-prone coding. Repetitious names, meanwhile, are

(for now, at least) essential for scraping functions.

Thus, be sure to export or prepare your dataset in such a way that the

related set(s) of variables you intend to use in dySEM have repetitious

names.

Double-Trouble with Dyadic Variable Names

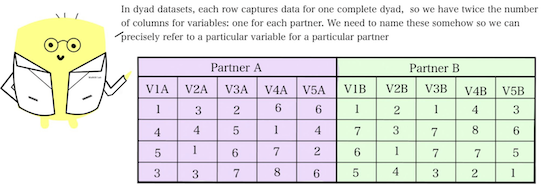

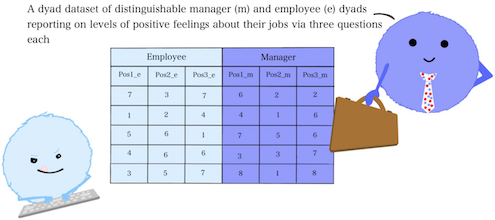

Variable names get a bit more complicated in the context of “dyad” (KENNY REF) or “=ide” (MLM REF) datasets, because these datasets contain the same variable twice, in two different columns: one for each member of a dyad.

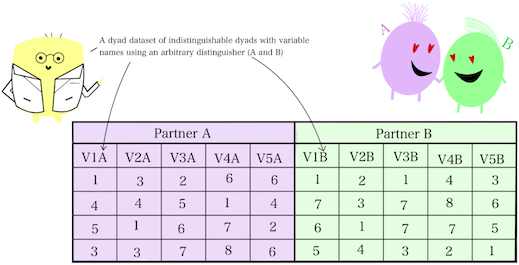

Each variable needs its own unique name, and so typically, dyad datasets involve appending a distinguishing character(s) or number(s) to make clear to which partner’s value a given variable refers. These distinguishers come in one of two varieties, corresponding to the type of dyads under study. If the dyads in the dataset are “indistinguishable”–that is, there’s no systematic and consistent way to assign dyad members to a particular role (e.g., friends, coworkers)–then distinguishers are usually arbitrary in name and designation. For example, some partner’s variables might be given the distinguisher “1” or “A”, while the other partner’s variables might be given the distinguisher “2” or “B”. The particular two distinguishers selected in these cases ultimately do not matter (as they do not convey any meaningful role-based information), as long as they are applied repetitiously between dyad members.

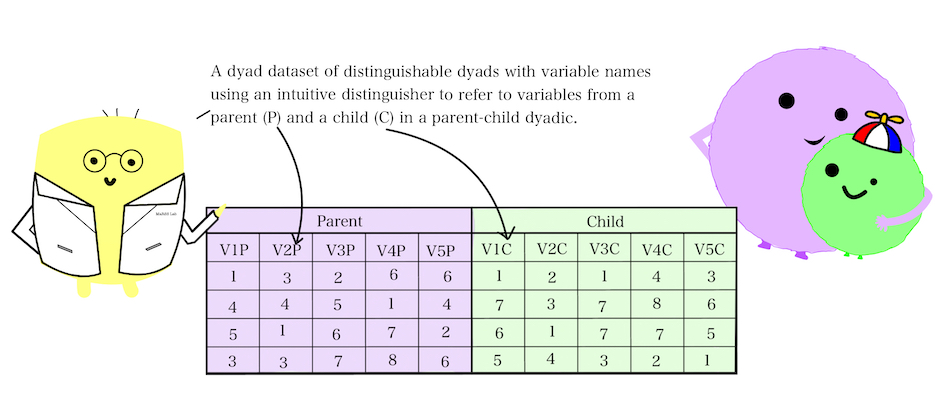

If, alternatively, the dyads in the dataset are “distinguishable”–that is, there’s a systematic role that defines members within a dyad (e.g., heterosexual romantic partners, parent and child, manager and employee, therapist and client)–then there is the opportunity for distinguishers for variable names to be selected for clarity to help you (and others) intuit which partner’s data is captured in which columns.

Dissecting Dyadic Dataset Variable Names

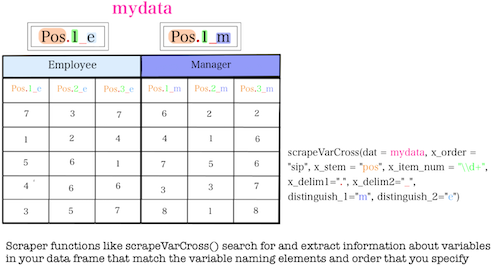

At this point, we have already previewed all of the major features of

a variable name in a dyadic dataset–we just need to bring them all

together. Understanding these specific features and the labels we use in

dySEM to refer to them will make it much easier for you when

you go to use a scraping function (e.g.,

scrapeVarCross()).

Let’s imagine a hypothetical dataset in which managers and employee dyads both reported on how positively they felt about their respective jobs, using a three-item questionnaire:

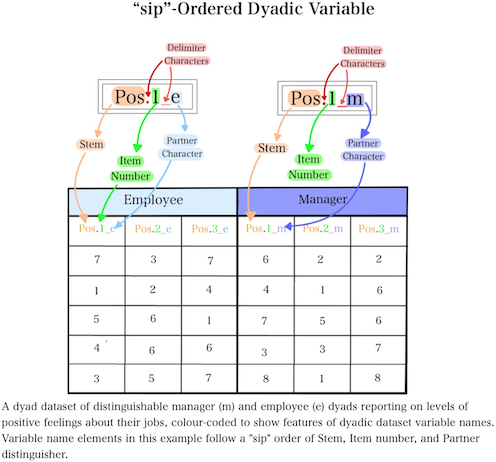

Breaking these names down, we are left with the following component features: The variable stem: characters that (ambiguous, or [ideally] intuitive) are consistent across all variables, for both partners that we are interested in (e.g., pos) The item number: a number that only appears twice (once per partner) that indicates which specific variable within those sharing its stem is being referenced (e.g., 2) And the partner distinguisher: the character that indicates which variables correspond to which partner (e.g., m or e) Delimiters such as “.” or “_” can also be used to separate the 1st feature from the 2nd, and the 2nd from the 3rd. Sometimes a name might include one delimiter; other times (as in this case), it might include two.

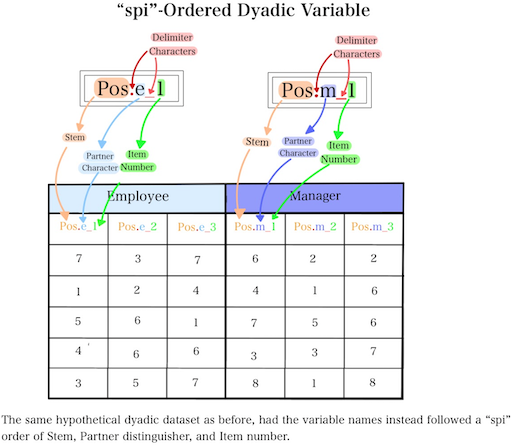

When dyadic dataset variable name features are arranged in this order (Stem, Item number, Partner distinguisher), we refer to them as “sip”-ordered when using dySEM. We do this because variable naming conventions are somewhat arbitrary and varied; people can and do arrange dyadic variable names in other orders. For example, another common ordering is Stem, Partner distinguisher, Item number, which we refer to as “spi”-ordered when using dySEM. “spi”-ordered variable names tend to be more common if you used an online survey program like Qualtrics to collect your data (e.g., with questions for both partners embedded in different sections of the same survey).

Spi-Ordered Dyadic Variable

If you can identity your variable stem, item number, and partner distinguishers (and any delimiters between these elements), and can correctly determine if your variable names are “sip”-ordered or “spi”-ordered, then you are all set to learn about the first step in using dySEM: scraping variable information. #link to the url for the scraping vignette